At best, load management should be done with trained professionals.

In the sport of football, the term "load management" is often used, but for the most part it is not entirely clear to the layperson what it actually means. In short, it is the planning of training and break times depending on factors such as load scope, intensity, frequency and individual work capacity. In addition, in the case of a structural injury, there is also the fact that we should respect the tissue healing phases.

Nevertheless, in the case of a groin strain, for example, we can already do more than one would think in the early stages of the injury.

As already touched upon, in the acute phase, high mechanical stimuli should be avoided. In this early phase of the injury (here: strain), light, cyclical movements are recommended, which cause little stress to the tissue and promote blood circulation.

Active rehabilitation can be started about 2-7 days after the injury (depending on the pain sensation). If the pain sensation allows it, one can also start isometric (holding) exercises during this period, in order to maintain or even increase the strength level of the affected muscles. In addition, isometric exercises can relieve pain in some people.

From the second week, dynamic exercises can be implemented, of course in consultation with the professional staff and the patient's own pain perception. If the movements still cause significant pain in the second week, or become persistent after the training (up to approx. 48 hrs. afterwards), then leave the ego at the door and take a step back again. Rehab is a marathon, not a sprint.

Estimated from week 3 on, you can usually start with some casual running training. The further steps like jumping, sprinting, change of direction and team training should be accompanied by experts*. A "return to play" test would be the gold standard here.

Disclaimer for this article

At this point we would like to leave another, final disclaimer. All statements regarding specific timing and exercise implications have been compiled by us based on research and experience.

They are neither fixed nor beyond any doubt. There are players who can start running and sprinting again after 7 days post-distraction. There will be players who can only return to such speed spectra after 4-5 weeks.

5 exercises for or to protect against groin injuries

Adductor Rock Back

You start in a kneeling position and spread one leg outward, supporting yourself with your hand on the floor.

Bringing your free arm under your torso, you first turn in. Then turn up by bringing your arm upward.

Repeat this exercise on both sides.

Copenhagen Hold

In this exercise, you perform a side plank on an elevation - benches, chairs or plyoboxes are particularly suitable for this.

Your upper leg rests on the box, while the free leg is lifted from the floor.

Repeat this exercise on the other side.

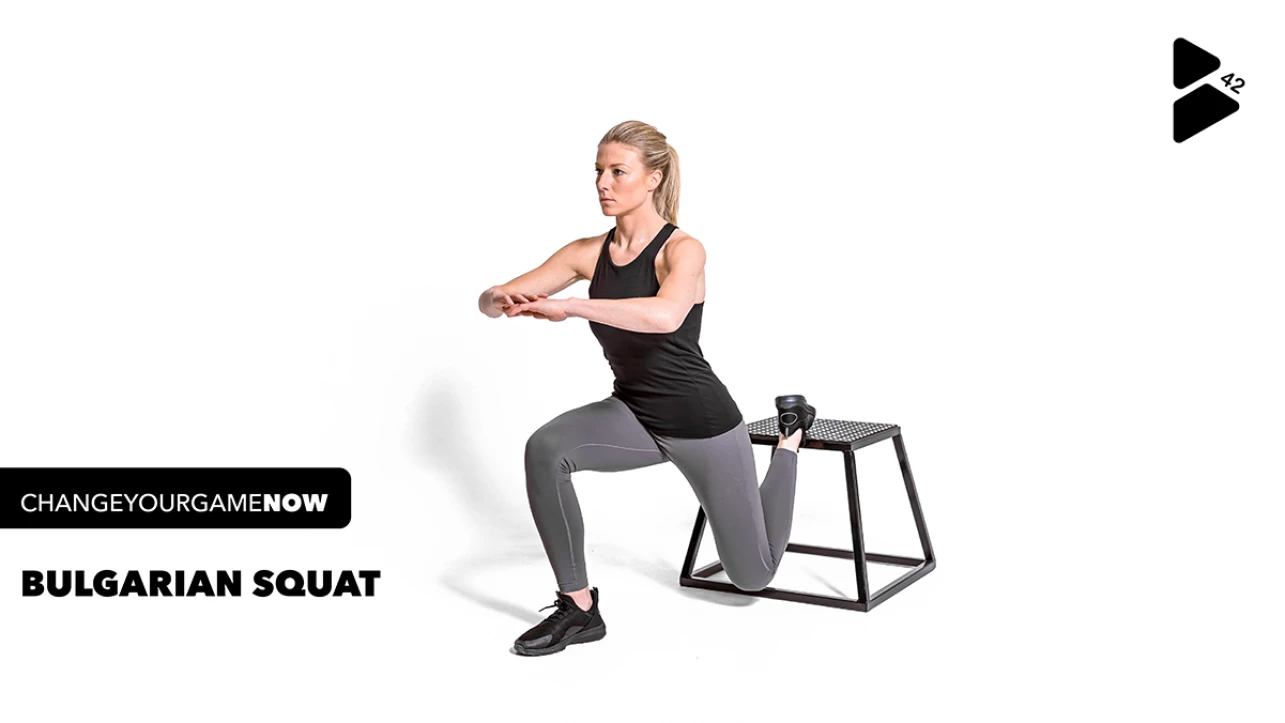

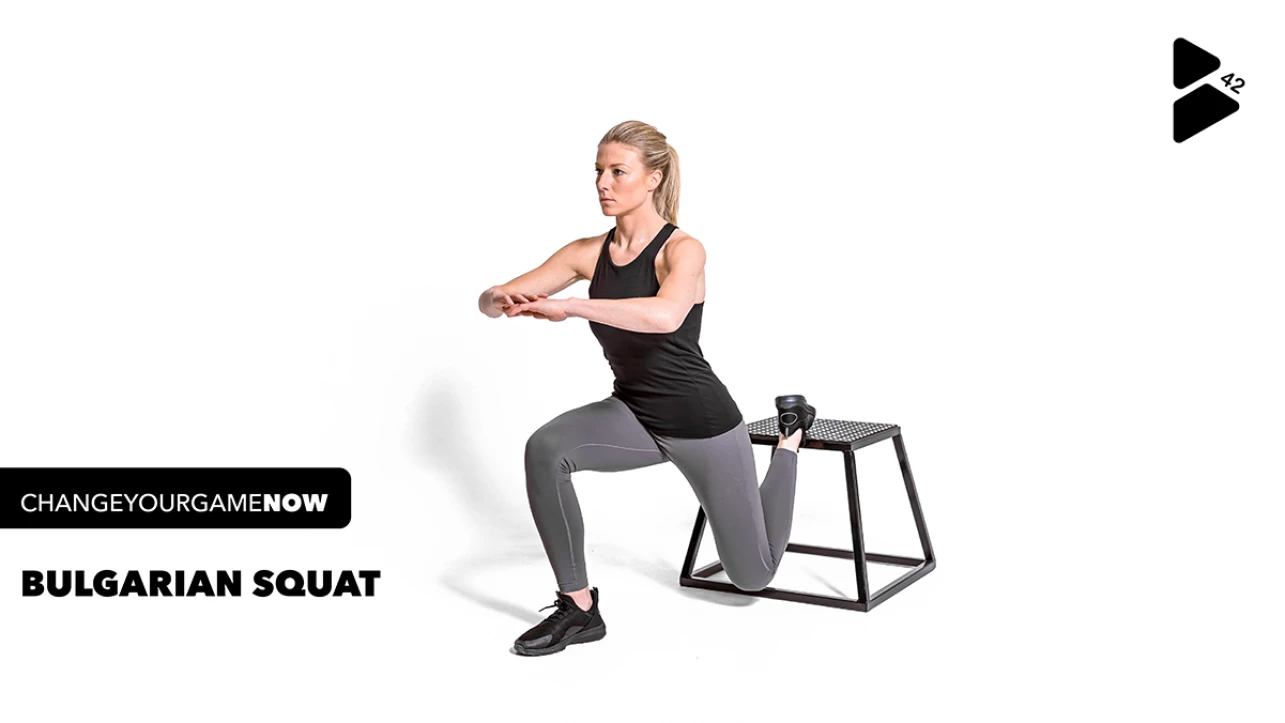

Bulgarian Squat

You start with one foot on a box or chair.

Then bend your front leg and extend it again. Ensure a stable upper body position and controlled flexion-extension movements.

Repeat this exercise on the other side.

Copenhagen Floor Elevation

Start the exercise lying on your side. Make sure your elbow is under your shoulder.

Then extend your upper leg and put tension on your adductors. Now bring your lower leg forward and bring it high and low.

Repeat this exercise on the other side as well.

Skater Jump

With skater jumps you jump from left to right. Land in a controlled manner and then explosively jump back to the side.

Make sure your upper body is stable and jump explosively from side to side.

About the author

Our author Lasse Ahl (33) has been actively playing soccer himself since he was 11 years old, and also does additive strength training as well as cycling, running and skiing.

He is a sports scientist (M.A.) at the University of Göttingen and has been working for several years in the university sports gym and at university sports.

Since 2017, he has also been the Academy Education Director responsible for the education and training of exercise instructors at the University of Göttingen in the areas of exercise science and basic physiology & anatomy.

Sources

Serner et al. (2020) Return to Sport After Criteria-Based Rehabilitation of Acute Adductor Injuries in Male Athletes

Volker Musahl, Jón Karlsson, Werner Krutsch, Bert R. Mandelbaum, João Espregueira-Mendes, Pieter d'Hooghe (2018) Return to Play in Football An Evidence-based Approachs