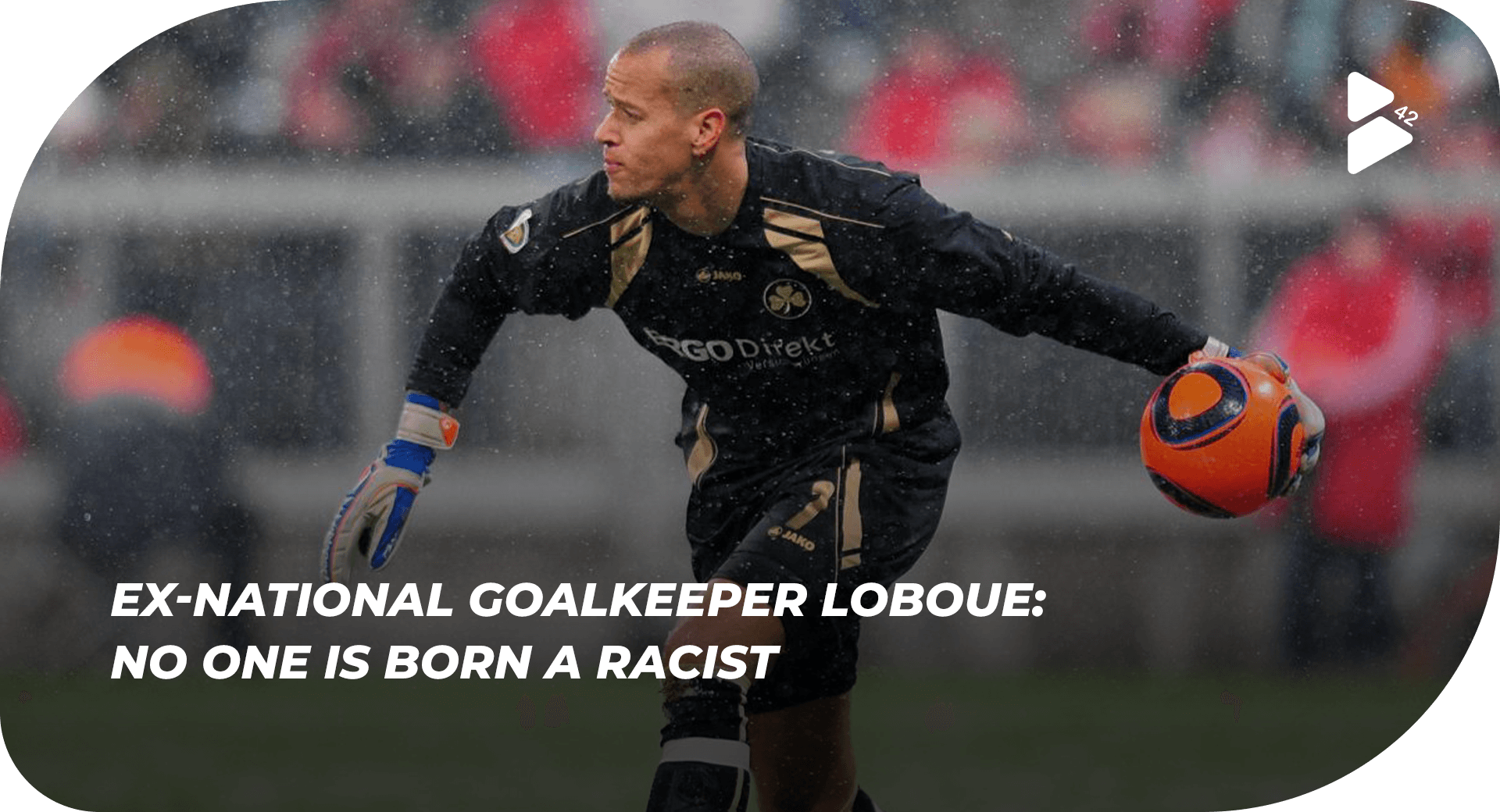

"No human being is born a racist"

Is there structural racism at the goalkeeper position? If a study by Humboldt University Berlin has its way, that's the case. And indeed, it is striking that - in contrast to all other team parts - there are no dark-skinned players in the first and second Bundesliga, especially in this so important position. We spoke to Stephan Loboué about this. The former number one at Spielvereinigung Greuther Fürth, who also played for the German U18 national team, is now a goalkeeping coach at Eintracht Frankfurt's youth development center. As the son of an Ivorian who grew up with his German mother in southern Germany, Loboué knows what racism means - nevertheless, optimism and, above all, the belief that football can change many things for the better prevail in him.

Stephan, how did you become a goalkeeper?

I was eleven or twelve years old. Before training, we boys would often play in front of the locker room - and I would stand in goal. Then the coach asked me if I would like to stand in goal during real training. I must have done pretty well, and it was clear: from now on, I'm a goalkeeper. I always wanted to get back out on the field and score goals, but the coach wouldn't let me.

You later turned professional and are now goalkeeper coach at Eintracht Frankfurt. How has the game of goalkeeping changed in recent years from your point of view?

Today, people talk about the modern goalkeeper who plays in the game. I can't quite understand this view. Jens Lehmann used to be my role model. Twenty-five years ago, he already played the way we expect goalkeepers to play today - even if he was an exception, of course. Of course, today you have to think more, more emphasis is placed on opening up the game and tactics, and goalkeepers are trained to be ambidextrous - that wasn't the case when I was young. But from my point of view, the difference is not as great as many people describe it.

You are the son of an Ivorian father and a German mother. You first decided to play for the German U-18 team, but later became an Ivory Coast national player. How did that come about?

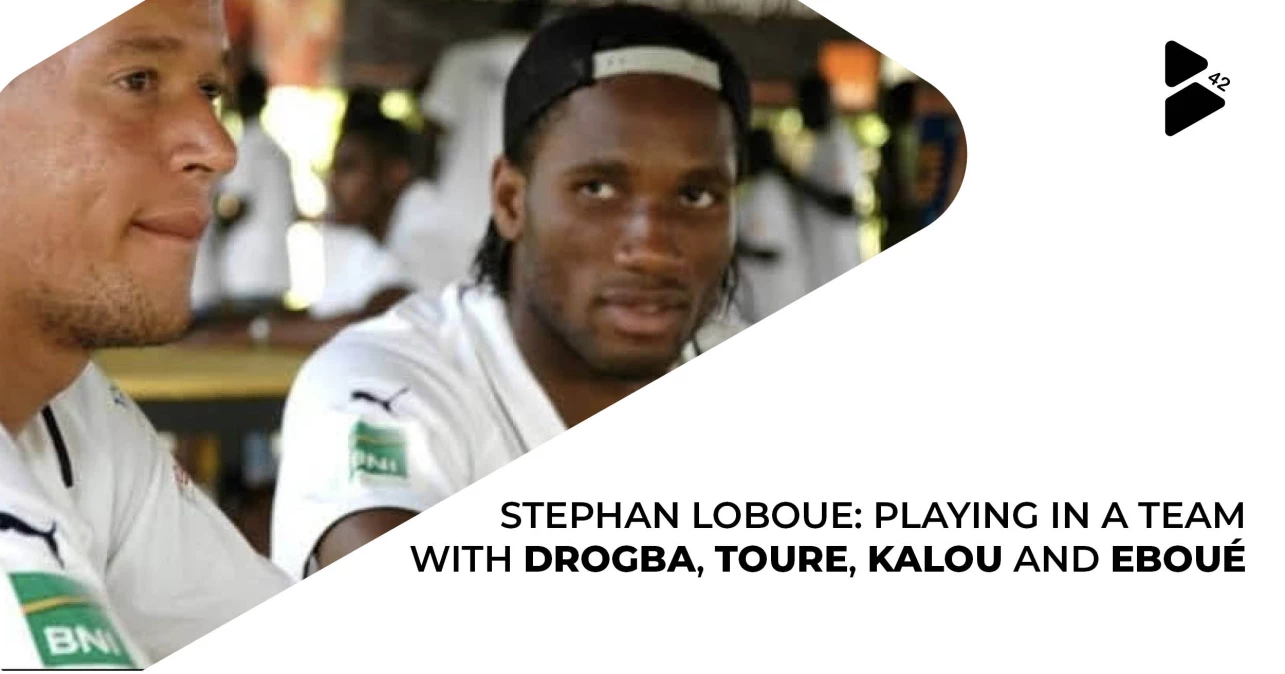

To be honest, I had no contact with the Ivory Coast. It was a matter of course for me to play for the German national team and a great honor. But in 2005, a consultant contacted me. He was asked by the Ivory Coast association if I could imagine playing for their national team.

And you saw that as a great opportunity?

Yes, of course. Oliver Kahn was too strong for me (laughs). And who wouldn't want to play with Drogba, Toure, Kalou or Eboué? My first international experience, albeit as a substitute, was in Spain in March 2006. I swapped gloves with Iker Casillas. Those are fond memories.

Unfortunately, we also have to talk about an unpleasant topic. In an interview with Der Spiegel, you commented on a study conducted by Humboldt University in Berlin that deals with racial stacking. It is argued that certain attributes are attributed to black football players and that it is a form of racism that there are no black goalkeepers in the first and second Bundesliga. Can you explain your position on this again?

I am the first black goalkeeper to have played in the national youth team. And unfortunately, not much has happened there, although there are definitely many good black goalkeepers. It's hard for me to call that racism, but obviously goalkeepers with darker skin are given less credit.

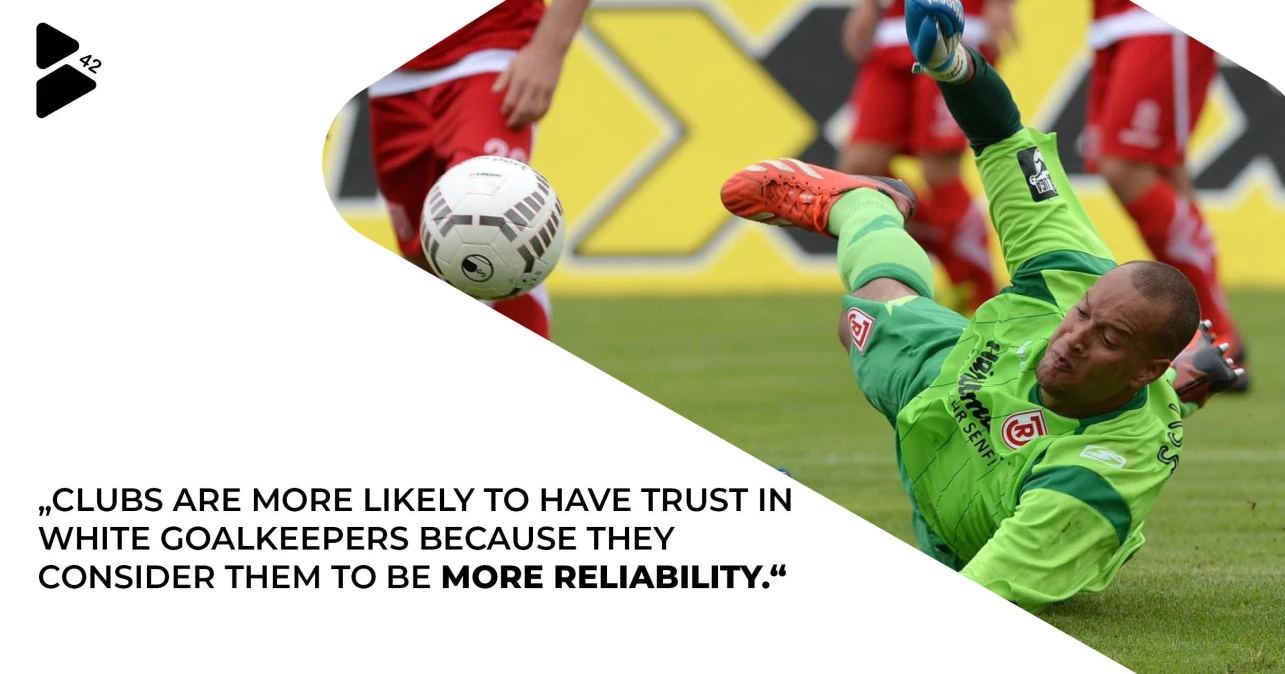

Has that also influenced your career? After all, you were voted the second-best goalkeeper in the second division at Greuther Fürth, but you didn't get an offer from the first division.

That's right. I was 26, a leading player and my contract was up. That's when you usually get at least one offer. I can't say it has a directly racist background, but I'm sure I would have had umpteen offers in England or France. Of course, in the end it's speculation, but a taint remains.

But that still doesn't answer why this is too obvious in the goalkeeper position, of all positions, while black footballers make up about 20 percent of players in other positions.

The goalkeeper position is one with a lot of responsibility. Any mistake can be game-changing. And apparently clubs tend to trust white goalkeepers more because they attribute more reliability and other virtues to them. I can't explain it any other way.

Have you had much experience with direct racism?

Absolutely. I've heard isolated monkey sounds in many stadiums - over and over again, from the first day to the last. But the situation has gotten better. Sensitivity is higher, much more is made public today - fortunately also outside the football pitch. A lot has happened there, although the refugee crisis has turned the social mood around again somewhat. But fortunately I don't perceive that on the football field.

But when you look at the racist hostility of the English players after the penalty shootout at the European Championship, are you worried that something like that could also happen in Germany?

Of course. There are few people who think like that, but there are still far too many. I actually rooted for all the dark-skinned players in the penalty shootout because I knew exactly what would happen if they missed.

To end on a positive note: Do you think football can also make an insanely positive difference here?

Absolutely. Football has an insane power. No one is born a racist. I see children from all different backgrounds playing football together here in Frankfurt. They don't think about it at all. Football has an incredible power, but also an incredible responsibility. We've already come a long way, but there's still more to do.